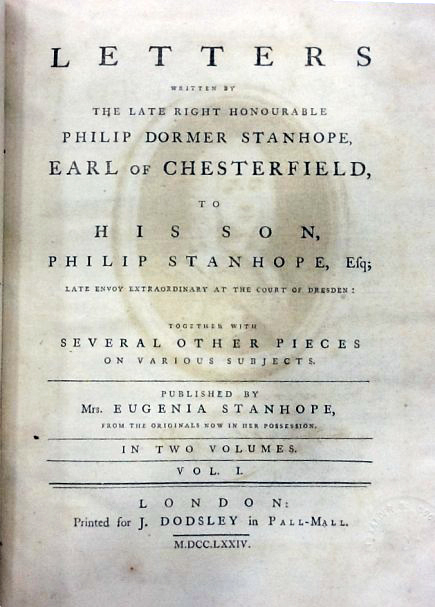

Philip Dormer Stanhope, Lord Chesterfield, is the second person to use picnic in English and spell it in a modern way. His son Philip wrote that he attended a picnic gathering at Madame Valentin’s salon, but his 1748 letter is lost. His father’s letter was published but buried among 262 others in the posthumous edition of The Letters of Philip Dormer Stanhope Letters in 1774. Chesterfield died in 1773 without ever mentioning picnic again.

Chesterfield was familiar with salon assembly but not a picnic. “I know that you go sometimes to Madame Valentin’s assembly,” Chesterfield wrote, “What do you do there? Do you play or sup, or is it only la belle conversation?” Philip’s lost reply surprised Chesterfield, who answered, “I like the description of your picnic, where, I take it for granted, that your cards are only to break the formality of a circle, and your symposium intended more to promote conversation than drinking. Though Chesterfield had many French contacts, he was unfamiliar with the Parisian custom of pique-nique.

In fact, picnic was an unfamiliar word among the English. It is omitted in Nathan Bailey’s An Etymological Dictionary (1721/1756) and Samuel Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language (1755). It was not until 1802 that the word was purposely publicized by the Pic Nics, a London-based theatrical/dining/gambling club.

See: The Letters of Philip Dormer Stanhope, Earl of Chesterfield to His Son Philip Stanhope, Esq., two vols. (London: J. Dodsley, 1774); The Letters of Philip Dormer Stanhope, Earl of Chesterfield to His Son on the Fine Art of Becoming a Man of the World and a Gentleman (1774). Edited by Oliver H. G. Leigh. Washington & London: M. Walter Dunne, 1901.; https://archive.org/stream/letterstohissono01chesuoft/letterstohissono01chesuoft_djvu.txt