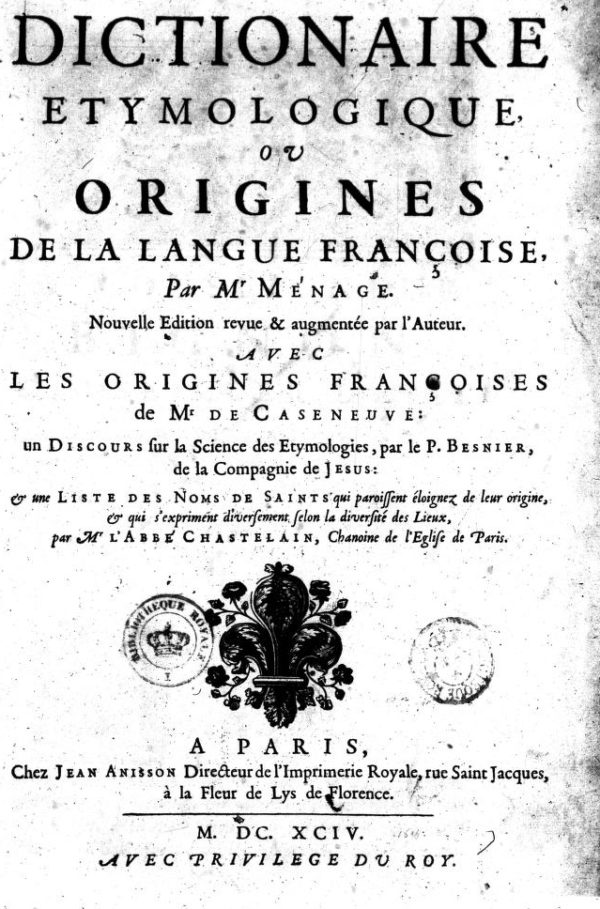

Gilles Ménage was the first to define piquenique in his Dictionnaire de Étymologique de la Langue Françoise, published in Paris in 1694. Forty-four years earlier, when he published his Les Origines de la Langue Françoise, piquenique, then newly coined in 1649, was an unknown word.

According to Ménage’s brief definition, piquenique was a Parisian dining custom, the chief attribute of which was contributing a portion of the meal or its cost. PIQUENIQUE. Nous disons faire un repas á piquenique, pour dire faire un repas òu chacun paye son écot : ce que les Flamans [Flemings] disent, parte bétal, chacun sa part. Ce mot n’est pas ancien dans notre Langue: & il est inconnu dans la pluspart de nos provinces. [PIQUENIQUE. We make a picnic meal, that is a meal where everyone pays his reckoning, as the Flemings say, pays their own his part. The word is not old in our language, and it is unknown in most Provinces.]

Piquenique was not included in the French Academy’s Dictionnaire de L’Académie Française until the third edition in 1740, when it was spelled as a hyphenated word pique-nique. The Academy’s editors paraphrased Ménage’s original definition, adding that the word was used adverbially, as in having a picnic dinner or a picnic meal. Without saying so, the presumption is that a picnic dinner is always indoors.

Neither Ménage nor the Académie offered a history of the word. Pique-nique was a dining style in which those at the table shared the cost of the meal’s food and beverages. Writing years later in his Confessions, Jean-Jacques Rousseau writes that in the 1740s, while living in Paris, he shared meals in picnic style with a friend. In his Reveries of a Solitary Walker, Rousseau recollects that he called dining in the picnic style at a restaurant. But in Emile (1762), a hugely popular novel, Rousseau describes an outdoor party he calls a festin, not a picnic.

In England, Oliver Goldsmith described a family enjoying light refreshments in an outdoor setting in the 1766 novel The Vicar of Wakefield. Like Rousseau, he does not claim this as a picnic because the word was as yet not adapted by the English. Eight years later, in Retaliation, a satirical poem, Goldsmith composed to respond to some of his critics, he begins with a reference to Paul Scarron, the French satirist reputed to have dined in the picnic style at his Parisian home. Goldsmith presumes that Scarron was hard up and could not otherwise entertain, so he dined in the picnic style. But Goldsmith doesn’t use the word instead, he follows Menage’s and the Academy’s definition:

Of old, when Scarron his companions invited,

Each guest brought his dish, and the feast was united;

If our landlord supplies us with beef, and with fish,

Let each guest bring himself, and he brings the best dish:

- In the court of Louis XIV, Ménage was socially adept and thoroughly argumentative. At various times, his circle included Parisian intellectuals and aristocrats; Madeleine De La Fayette, author of The Princess of Cleves (1678), the Duc de la Rochefoucauld, author of Maxims (1665/78), Françoise d’Aubigné, who married Paul Scarron (1651) and later became Madame de Maintenon, Louis’ mistress and morganatic wife. Ménage is now usually referenced as Vadius, a character satirized in Molière’s The Learned Women (1672). Vadius’ brief appearance casts him as being nasty and caustic; his parting words to rival poets define his inflated pedantry, “I defy you in verse, prose, Greek and Latin.”

See: This, according to Isabelle Leroy-Turcan. “L’information du Dictionnaire Étymologique ou Origines de la Langue Française de Gilles Ménage” (1996); Jean-Jacques Rousseau. ‘Livre VII’, Les Confessions (1789). Jean-Jacques Rousseau. “Book 11,” The Confessions Trans. by J. M. Cohen. Baltimore (1954); Oliver Goldsmith, Retaliation; a poem (1774)