Picnickers will be satisfied only with “a perfect day for a picnic.” Spring or summer is preferred, but any season will do. Outdoors is preferred to the indoors, anywhere – on land or a sea, in backyards or parks, on beaches or rooftops—wherever a space can be found to spread a blanket or set a table and chairs. The perfect day is summery and clement; there is a light breeze to mitigate heat and rustle leaves; the sky is clear with a scattering of clouds. The picnic blanket is set on the grass beneath the shade of a large tree beside a stream or nearby water. Birds sing; a breeze moves the foliage. Incredibly, perfect picnics happen often enough so that they are expected—rain, cold, or ants to the contrary.

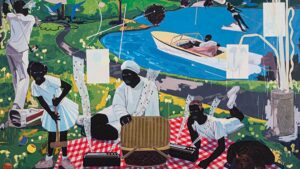

James Kerry Marshall. Past Times (1997)

Among picnic aficionados, there are some hard and fast opinions.

Georgina Battiscombe’s 1949 English Picnics is a standard discussion of English picnics in literature and art. Battiscombe asserts the English picnicker “is a devotee of the simple life; for a brief moment, he apes the noble savage. Before the Romantics had made nature fashionable no one connected the idea of pleasure with the notion of a meal eaten anywhere except under a roof.” (Probably, Battiscombe did not believe this hyperbole because her examples disprove this assertion.)

James Beard’s first picnic book, Cook It Outdoors (1941), if you never picnicked, begins with a perfunctory statement about picnics –how to cook outdoors, staking your turf, and, incredibly, how to build a stone fireplace (!). He suggests that it’s not necessary to link foods with the picnic so that you have freedom of choice that does not exist for home entertaining. “Throw anything at hand into a picnic basket,” he says, “drive or walk to the wildest place imaginable,” then “flop on the grass or the beach and be absolutely relaxed and carefree.” He affirms that “Picnics are a cult. Either you adore them and eat on the wing two or three times a week, when the weather permits, or you staunchly and bravely bear them once or twice a year.” His four cardinal rules for picnicking are: make the picnic to suit your guests; contrast your foods with ordinary daily fare; prepare “oceans of food,” and finally, “Don’t be in a hurry.” (The italics are Beard’s.) His second picnic book is The Complete Book of Outdoor Cookery (1955), and his third, Menus for Entertaining (1965). Beard’s credo was “Wherever it is done, picnicking can be one of the supreme pleasures of outdoor life. . . Have a picnic at the slightest excuse.”

Beard’s 1941 picnic “rules” listed in Cook It Outdoors are his first attempt at setting the record for what he later calls the cult of picnicking.

1. The company is one of the most important factors in the successful picnic. A formal group needs a formal picnic, and vice versa.

2. The food should be as much of a contrast to your daily menu as the surroundings in which you eat are to your own dining room.

3. Picnic appetites are usually stupendous–be sure that you have oceans of food. The same goes for the liquid side of the house, be it alcohol or not.

4. Don’t be in a hurry.”

In 1965, Beard’s Menus for Entertaining asserts a picnic requires that you travel somewhere to eat. He even suggests eating a car while sightseeing, though this might prove messy.

When Elizabeth David was 27, she briefly settled in Antibes, where she befriended seventy-two-year-old Norman Douglas. Together they the hills above Antibes where they casually picnicked: he carried cheese in his pockets, and they would stop for wine. In her 1950 A Book of Mediterranean Food, David realized the elements of her ideal and described it in “Eating Out in Provincial France.” “There has to be water,” she declares, “and from that point of view, France is wonderful picnic country, so rich in magnificent rivers, waterfalls, reservoirs, that it is rare not to be able to find some delicious spot where you can sit by the water, watch dragonflies and listen to the birds or to the beguiling sound of a fast-flowing stream. As you drink wine from a tumbler, sprinkle your bread with olive oil and salt, and eat it with ripe tomatoes or rough country sausage, you feel better off than in even the most perfect restaurant.” For 1955 Summer Cooking, David claims “picnic addicts” fall in two categories “roughly divided between those who frankly make elaborate preparations and leave nothing to chance, and those others whose organization is no less complicated but who are more deceitful and pretend that everything will be obtained on the spot and cooked over a woodcutter’s fire conveniently at hand; there are even those, according to Richard Jefferies, who wisely take the precaution of visiting the site of their intended picnic some days beforehand and there burying the champagne.”

M.F.K. Fisher’s “The Pleasures of Picnics” (1957) argues that there are “true” picnics. Fisher’s premises are: that picnics must be eaten outdoors, but not all alfresco meals are picnics; you must leave home for a picnic; a real picnic is always a feast; the true picnic must always have a bit of hazard about it, such as ants, rough ground, etc.; there must be company; the food must be the best obtainable; the best time of day to picnic is twilight in midsummer; midday day in April or May or October; it is preferable that food should be eaten with fingers; there must be sandwiches; and they must be jolly. Fisher is adamant that people who do not like picnics must be “dismissed immediately.”

Food is served at once, whether picnickers are reclining on rugs or blankets or seat at tables. This type of service is probably a result of convenience, though it might be a variation of French service in which all the foods are placed on the table to be passed around to diners. Some might also call it the “boarding house” style of service. Picnickers serve themselves as they please.

Seating arrangements are usually informal, and only formal may have assigned seats. There is no head of the table unless the picnic is indoors. A British diplomat, Gertrude Bell enjoyed a breakfast picnic in the desert with King Faisal of Iraq. Bell sat cross-legged in Arab style.

Gertrude Bell (in Western garb) with King Faisal and British military officers at Tel ‘Aquar Quf (August 1921)

Princess Margaret liked comfort; “In my opinion,” she says, “picnics should always be eaten at a table and sitting on a chair.” A picture-perfect picnic is a group seated around the edges of a blanket, the center of which is laden with food and drink. Such a scene is the subject of Hungarian painter Paul Szinyei Merse’s 1873 Mayfair (Featured)

Dress code is as-you-will, usually informal. Nevertheless, dress codes may be socially and hierarchically regulated. Edouard Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass (1863) mocks picnic dress codes while suggesting that anything goes at a picnic, especially sexual assignations.

Picnicking requires food preparation, a selection of baskets or hampers and such for carrying food, supplies for cooking, and the requisite items for serving. Except for modern technologies (thermos containers, insulated baskets, propane stoves, plastic utensils, and the like), the necessities for a picnic are universal and essentially unchanged. Preparation and service of picnic foods may be casual or cosmopolitan, regardless of social class, wealth, or education: sandwiches, canned soda, and beer thrown into a paper bag, or elaborate baskets fitted with coolers for pâté and roasts and crystal stemware for wine and champagne.

For most picnickers, the chief problem with picnics is that they are too short. They are ephemeral—a luncheon, an afternoon, perhaps an entire day.