Piedmont, West Virginia, where Gates spent his youth, was a segregated town where most of the inhabitants worked at a Westvaco paper mill.

Though Gates looks fondly at the company picnic scheduled to close in 1969 or 1970, the event is bittersweet. It’s described in the last chapter of the book, which, he explains, is written so that his children will know about the town and place his father grew up in and the way of life of the people there.

“The town will die [when the mill closes], but our people will not move, “Gates writes. “They will not be moved. Because for them, Piedmont [Mineral County, West Virginia]- snuggled between the Allegheny Mountains and the Potomac River Valley — is life itself.” When the mill closed, Piedmont’s population dwindled from 22,00 to 1100. At its zenith, there were 351 inhabitants of color.

Company picnics were always segregated. The white company picnic was held ten miles away, a distance the Westvaco administration considered appropriate.

Gates writes, “I wish I could say that they community rebelled, that everyone refused to budge, that we joined hands in a circle and sang “We Shall Not, We Shall Not Be Moved,” followed by “We Shall Over Come.” But we didn’t. People preferred not to acknowledge the approaching end, as if a miracle could happen and this whole nightmare would go away.”

The picnic adheres tightly to tradition: the same farm location, cars parked in the same places, and the food always the same boiled corn, fried chicken, lemonade, coffee with sweet cream, and whiskey bottles nestled in paper bags. “The young folks go swimming. Freddy Taylor plays rhythm and blues on the guitar. Miss Sarah Russell wanders about preaching. There are no speeches, no fights, even when Inez Jones dances the “dirty dog.”

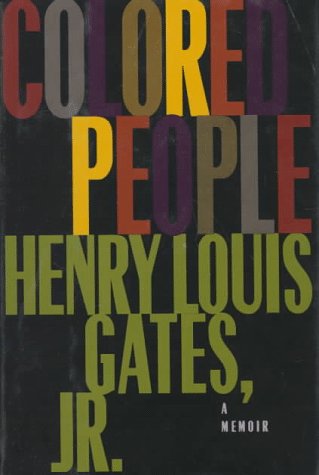

See Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Colored People: A Memoir New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994