Woolf’s picnic on the summit of Monte Rosa, a fictional place in South America, is the high point (pun intended) of The Voyage Out (1915). Journeying on donkeys walking in a single file, the narrator creates the image of “a jointed caterpillar, tufted with the white parasols of the ladies, and the Panama hats of the gentlemen.” *

The view from the summit is “splendid,” but the picnickers are buffeted by the wind so that their tablecloth is spread in the lee of a ruined wall where they lunch on cold chicken, sandwiches, wine, fruit, bananas, and tea. The mood is jolly, especially when “… Miss Allan, who was seated with her back to the ruined wall, put down her sandwich, picked something off her neck, and remarked, “I’m covered with little creatures.”

As the ants arrive, “pouring down a glacier of loose earth heaped between the stones of the ruin-large brown ants with polished bodies,” the picnickers retaliate. “The tablecloth represented the invaded country, and round it, they built barricades of baskets, set up the wine bottles in a rampart, made fortifications of bread, and dug fosses of salt.” When ants get through, they are bombarded with breadcrumbs. Battling the ants becomes a game that removes the veneer of decorum that usually inhibits good society. Mr. Perrott removes an ant from Evelyn’s neck, and Mrs. Elliot remarks confidentially to Mrs. Thornbury that it would be no laughing matter “if an ant did get between the vest and the skin.”

This amusement is short-lived. And the descent of uneventful and the picnickers separate without incident.

Subsequently, Rachel Vinrace pairs off with Terrence Hewitt. It’s an erratic relationship with a downward spiral that ends when she contracts jungle fever. Confined to bed, she lingers for ten days and dies during a severe thunderstorm.

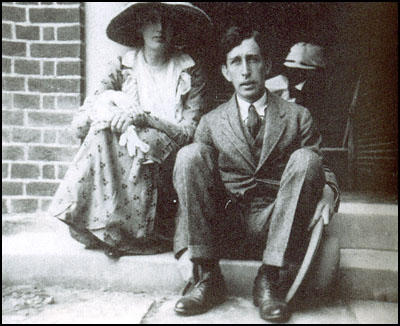

Woolf’s decision to “kill’ her fictional heroine was a figurative response to her troubles. Before it was finally published in 1915, the novel’s narrative sputtered tortuously. When she married Leonard Woolf in 1912, she spun headlong into a deep depression instead of smoothing her troubles. Even the title, The Voyage Out, suggests Woolf is searching to resolve her fiction problems if not in life. After suffering multiple suicide attempts, she eventually persevered until her successful suicide in 1941.

*Monte Rosa is fictional in the novel’s context, but it is the second-highest mountain in the Alps. She knew her father, Leslie Stephen’s Playground of Europe, a mountaineering classic about climbing in the Alps. Her caterpillar metaphor is an improvement in his observation of alpine climbers. “I watched,” he wrote, “through a telescope, the small black dot, which was men, creeping up the high flanks of Monte Rosa or Mont Blanc.”

An informal pose for a very newly married couple. Three years later, she suffered a deep year-long depression.

Featured Image: Terrence Hewett’s invitation for a picnic on Monte Rosa.

See Virginia Woolf. The Voyage Out. London: Duckworth, 1915; Leslie Stephen. Playground of Europe. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1871.