Dickens does not use the word picnic. But when the Wardles have lunch in their barouche, it’s an unmistakably a picnic: “In an open barouche, the horses of which had been taken out, the better to accommodate it to the crowded place, stood a stout old gentleman, in a blue coat and bright buttons, corduroy breeches and top-boots, two young ladies in scarfs and feathers, a young gentleman apparently enamoured of one of the young ladies in scarfs and feathers, a lady of doubtful age, probably the aunt of the aforesaid, and Mr. Tupman, as easy and unconcerned as if he had belonged to the family from the first moments of his infancy. Fastened up behind the barouche was a hamper of spacious dimensions—one of those hampers which always awakens in a contemplative mind associations connected with cold fowls, tongues, and bottles of wine—and on the box sat a fat and red-faced boy, in a state of somnolence, whom no speculative observer could have regarded for an instant without setting down as the official dispenser of the contents of the before-mentioned hamper, when the proper time for their consumption should arrive.”

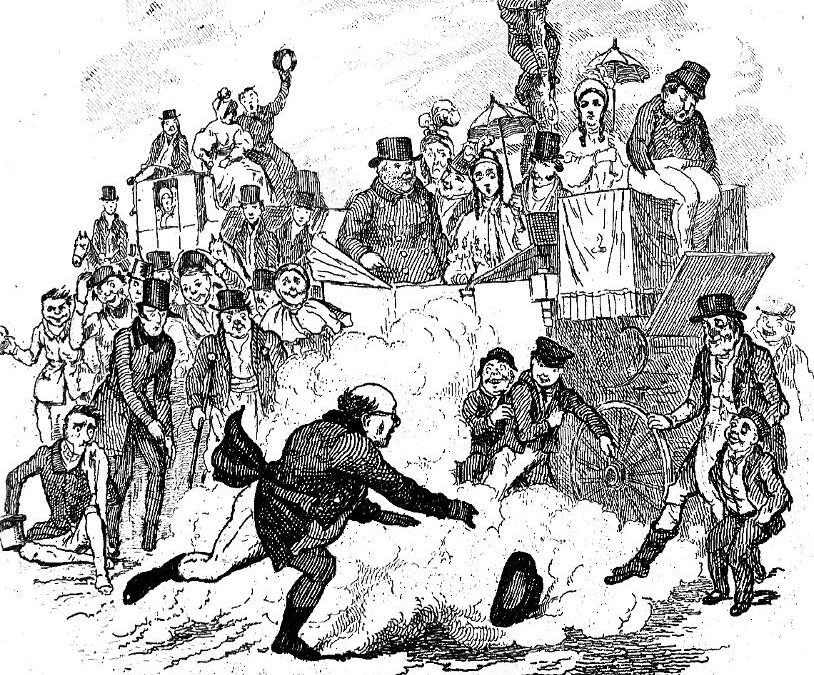

While watching a grand entertainment of a military re-enactment and a parade, Samuel Pickwick loses his hat and cannot reasonably retrieve it despite his best effort. Not used to any exertion and exhausted, Pickwick is fortunately saved when the hat blows into the wheel of a barouche belonging to Wardles, a family of four, who are about to be served a picnic of cold fowls, pigeon pie, veal, ham, tongue, lobster salad, and wine.

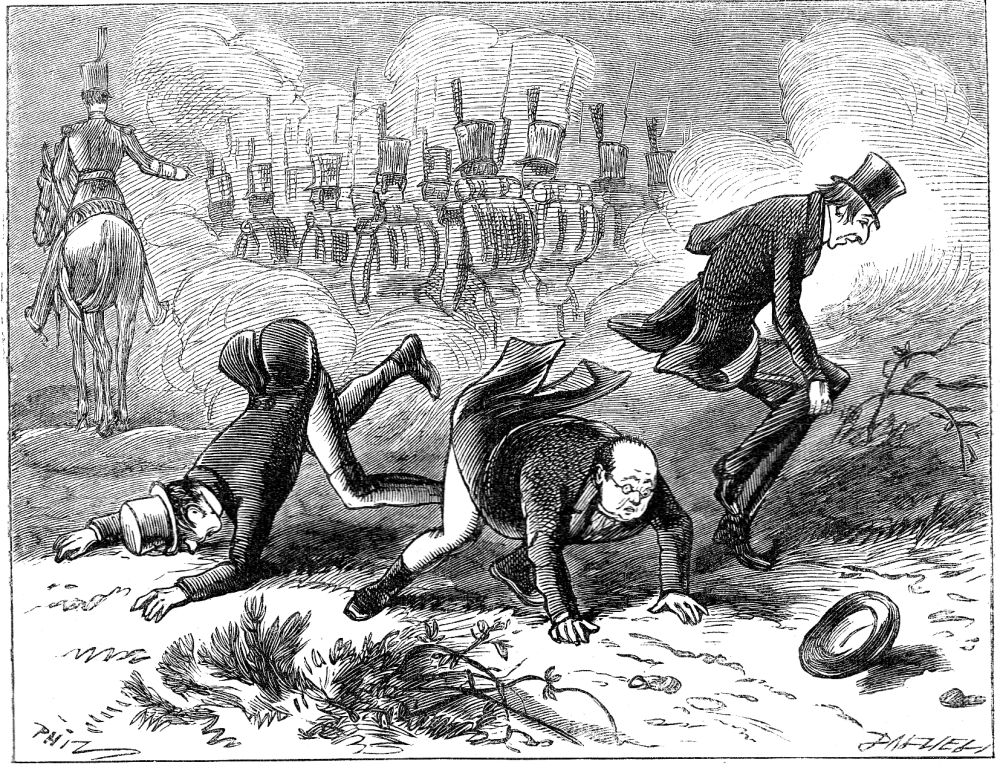

Hablot Knight Browne (‘Phiz’), ‘Mr. Pickwick in Chase of his Hat” (1836)

Gracious to a fault, Mr. Wardles invites Pickwick and friends, Winkle, Snodgrass, and Jingle, to join their luncheon. So squinching in, they sit with plates and glasses and flatware balancing on their knees, waiting to be served by a fat boy named Joe, who can barely keep from falling asleep: Now, Joe, knives and forks.’ The knives and forks were handed in, and the ladies and gentlemen inside, and Mr. Winkle on the box, were each furnished with those proper instruments.

‘Plates, Joe, plates.’ A similar process employed in the distribution of the crockery.

‘Now, Joe, the fowls. Damn that boy; he’s gone to sleep again. Joe! Joe!’ (Sundry taps on the head with a stick, and the fat boy, with some difficulty, roused from his lethargy.) ‘Come, hand in the eatables.’

Featured Image: Robert Seymour’s “Mr Pickwick in Chase of His Hat”

See Charles Dickens. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Robert Seymour. London: Chapman and Hall, 1837. Usually referred to as The Pickwick Papers.; http://www.gutenberg.org/files/580/580-h/580-h.htm; https://archive.org/details/postpapers01dickuoft; https://archive.org/stream/postpapers01dickuoft/postpapers01dickuoft_djvu.txt

* Dickens’s Pickwick Papers is a kind of picnic novel. It has no beginning or end, and all of the stories might stand alone, though in book format, they are all served at once in picnic style.