If you think hot dogs, fried chicken, or ham sandwiches are prime picnic foods, think again. A (brief) survey of picnic menus reveals preferences are limited only by one’s imagination, expense, preparation, and appetite.

There is an ongoing conversation, some would call it a debate, about whether the foods should be simple or complex. More often, however, it’s debated whether picnic food can be store-bought, home-cooked, or cooked on-site. It’s also debated where to picnic, but that’s a discussion for another time.

When Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin described haltes de chasse, the midday hunters’s alfresco lunch in Physiologie du Gout or The Psychology of Taste, he writes that they may be enjoyed informally and sophisticated. Of the former, when hunters reach their trysting place, they pause and lunch on little well-baked loaves, cold chicken, the pieces of Gruyere or Roquefort, and white wine. The festive portion of the halte de chasse begins when the caléches arrive with family, friends, and staff ready to serve a small feast of pâtés de Perigord, Strasbourg charcuterie, patisseries from Chez Achard, and foaming champagne. Gustave Courbet’s Le Repas de chasse (1858) provides a variation of Brillat-Savarin’s haltes de chasse. The luncheon includes a large roast, a knife and a fork beside it; large dinner plates; a basket of fruit, and several bottles of wine. A servant kneels, retrieving more wine and cooling it in the stream.

Not for the faint-hearted is Mrs. Elizabeth Beeton’s “Bill of Fare for 40 Persons,” which requires extensive preparation, cooking that requires transportation, staff, and disregard of cost:

- A joint of cold roast beef, a joint of cold boiled beef, 2 ribs of lamb, 2 shoulders of lamb, 4 roast fowls, 2 roast ducks, 1 ham, 1 tongue, 2 veal-and-ham pies, 2 pigeon pies, 6 medium-sized lobsters, 1 piece of collared calf’s head, 18 lettuces, 6 baskets of salad, 6 cucumbers.

- Stewed fruit well sweetened, and put into glass bottles well corked; 3 or 4 dozen plain pastry biscuits to eat with the stewed fruit, 2 dozen fruit turnovers, 4 dozen cheesecakes, 2 cold cabinet puddings in moulds, 2 blancmanges in moulds, a few jam puffs, 1 large cold plum-pudding (this must be good), a few baskets of fresh fruit, 3 dozen plain biscuits, a piece of cheese, 6 lbs. of butter (this, of course, includes the butter for tea), 4 quartern loaves of household broad, 3 dozen rolls, 6 loaves of tin bread (for tea), 2 plain plum cakes, 2 pound cakes,2 sponge cakes, a tin of mixed biscuits, 1/2 lb., of tea. Coffee is not suitable for a picnic, as it is difficult to make.

For his three-day picnic binge, W.C. Fields is supposed to pack watercress, chopped olives and nuts, tongue, peanut butter, strawberry preserves, deviled eggs, spiced ham sandwiches, celery stuffed with Roquefort cheese, black caviar, pâté de foie gras, anchovies; smoked oysters, baby shrimps, and crabmeat, tinned lobster, potted chicken and turkey, Swiss, Liederkranz, and camembert cheeses, olives, three or four jars of glazed fruit, angel food and devil’s food cakes, gin, wine, and a case of Lanson champagne.

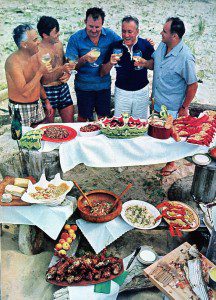

“The Five Chefs’s Picnic” in the summer of 1966, organized by Claiborne and Pierre Freney, was cooked and served on the beach of Gardiners Island. Transportation involved trucks and boats to the beach, where the five chefs prepared and served: Mussels Ravigote, Pâté Bluefish au Vin Blanc. Beef Salad, Seviche, Poached Striped Bass with Sauce Rouille, Grilled Squab [fifteen], Cold Stuffed Lobster, Mélange of Fruits. Assorted Cheeses [Brie, Camembert, goat cheese], French Bread, Chablis, Beaujolais Supérieur.

Mark Kauffman. “Magnificent Pique-Nique: Five Celebrated Chefs on a Cookout.” (1965)

Ford Maddox Ford’s travelogue in Provence describes a picnic on a Mediterranean calanque, a rocky inlet like a fjord, at which fifteen prodigal picnickers consumed fifty pounds of bouillabaisse, twelve cocks stewed in wine with innumerable savoury herbs, “a salad as big as a cartwheel,” sweet-cream cheese with a sauce made of marc and sweetherbs, apples, peaches, figs, and fresh grapes.

Martin Amis’s drug-addled gourmand picnickers in Dead Babies consumed beef steak sandwiches, sardines, liver sausage, anchovies, hard-boiled eggs, crispbread with smoked salmon, salad, celery, radishes, cheese, apples, bananas, biscuits, six bottles each of Pouilly Fuissé, St. Emilion, and Chateau Neuf de Pape, one Glenfiddich, one Gordon’s Gin, and one Napoleon Brandy.

A sampling of food writers’s suggestions, none of which are quickie menus.

The first cookbook dedicated to picnics, Linda Larned’s 1913 One Hundred Picnic Suggestions, does not recommend cooking out. She divides her food into things for a picnic basket or a “motor hamper,” implying that motorists are more food-savvy and richer. There are many suggestions for cold sandwiches and salads, but for motorists, she’s enthusiastic about hot foods. Instead of tuna or ham sandwiches, she suggests lobster creole, calf’s liver terrapin, or deep-fried cheese cutlets.

Elizabeth David’s Summer Cooking describes her picnic in France just after the end of World War II. Everything was store-bought: olives, anchovies, salami sausages, pâtés, yards of bread, smoked fish, fruit, cheese, and “cheap red wine.”

James Beard’s Menus for Entertaining suggests that a “Festive Country or Beach Picnic for –8” to be served with attractive plates, good cutlery, and crystal, and includes stuffed tomatoes, veal and pork terrine, beef à la Mode Gelée, potato salad or green salad, French bread, butter, cheese, fruit, angel food cake. Beverages suggested are lightly cooled Beaujolais or California reds, cognac, and kirsch to go with a great hot or iced coffee vacuum bottle.

In The Picnic Book, Nika Hazleton divulges that her favorite place to picnic is in ruins, “of all of the picnic sites in the world, a set of handsome ruins …appeals to me most.” Her menu and recipes for a picnic in ruins include Smoked Trout, Leaves of Bibb Lettuce Stuffed with Cream Cheese, Cold Sliced Steak, and Cucumber Stuffed with Tomatoes, Mushroom Salad, French Bread, Bitter Chocolate, and Fresh Apricots.

Constance Spry and Rosemary Hume’s The Constance Spry Cookery Book put little stock in Mrs. Beeton and curtly suggest that elaborate picnic baskets are “just transported meals—plate, food, champagne, and footmen all complete. This is not the best way to enjoy a picnic.” For those seeking more relaxed suggestions, Spry and Hume suggest a simple picnic of a French Roll with bananas and chutney, a Triple-decker Sandwich, Omlette on a roll, Cornish Pasties, Hamburgers, and Ginger Cake.

Claudia Roden’s Picnic, The Complete Guide To Outdoor Food includes a menu for a picnic at the Glyndebourne Festival Opera, suggested by a friend. It’s an elaborate meal that Roden says is fitting for an elaborate locale. Roden includes recipes for Mousse de Caviare, Chaufroid de canard, Tomates Fracies, Pêches aux fraises, and champagne of your choice.

Alice Waters’ Chez Panisse Menu Cookbook, “Picnic Menu for Six” includes Roasted Red Peppers with Anchovies; Potato and Truffle Salad; Hard-Cooked Quail Eggs; Marinated cheese with Olives and whole Garlic; Roasted Pigeon and purple grapes; Sourdough Bread and Parsley Butter; Lindsey’s Almond Tart; Nectarines; and red or white French wines with the meal and a Provençal, Muscat Beaunes-de-Venise with the dessert.

Among epicures, William Blanchard Jerrold wrote the menu with heavy satiric humor in “Picnic Reform,” an entry in The Epicure’s Yearbook for 1869, about how he realized his local West End London food emporium was his best picnic food source. Blanchard calls this new picnic fare “Potted Luck” because it all comes in tins, and suggests picnickers purchase stuff like “Potage—Crecy. Vermouth de Turin, Hors d’oeuvres. — Salade d’anchois; salade de homard; caviare; saucisson de Brunswick; saucisson de Strasbourg aux truffes; anchois frais; ecrevisse; potted tongue. . .” and much more.

Featured Image: Édouard Manet. Le déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863). The picnic foods suggest a symbolic sexual liaison: oysters are aphrodisiacs; cherries and peaches have suggestive contours that resemble the female torso, and the overturned basket may suggest loss of innocence.