First coined in Paris, pique-nique appeared in a vers burlesque published in Paris during the War of the Fronde in 1649. Pique-Nique was the nickname given to a musketeer who turned gourmand and the Bacchic eating and drinking club, whose members shared expenses, chacun en paysant sa dépense. Pique-Nique’s identity is now unknown.

Fifty years later, piquenique, no longer a man’s name, morphed into a Parisian dining style where guests either shared expenses or contributed some portion. Un repas à piquenique, was never outdoors. It was officially included listed in Ménage’s 1694, standard French dictionary as PIQUENIQUE Nous disons faire un repas à piquenique pour dire faire un repas où chacun paye son écot ce que les Flamans disènt parte vital chacun fa part. Ce mot n eft pas ancien dans notre Langue & il eft inconnu dans la pluspart de nos Provinces.

Though picnic is a phonetic adaptation of pique-nique, the French used the word only to describe an indoor meal at home or in a restaurant. For outdoor picnics, the French used euphemisms such as déjeuner sur l’herbe, repas de chasse, partie de campagne of which Edouard Manet’s Le déjeuner sur L’herbe is the prime example. Manet never explained why he used an outdoor setting for a sexual assignation. Italians used merenda or scampagnata, a holiday or a trip to the country, or lolazione sull’erba, luncheon on the grass. Until the 20th century, the Spanish used merienda, never a picnic as in the title of Francisco Goya’s Merienda a orillas del Manzanares. Goya settled on outdoor entertainment because it was a recognizable social activity, like hunting or dancing. Now, merienda is a snack and not a meal.

Francesco de Goya.La merienda a orillas del Manzanares (1776). Oil on Canvas. Madrid : Museo del Prado

In English or French, Picnic is presumed to be a compound word. But when it originally appeared in 1649, it was hyphenated. Forty-five years later, it was one word in Menage’s Dictionnaire du Etymologique de la Langue Françoise. Currently, it is one word in English and hyphenated in French. The Oxford English Dictionary offers a comprehensive denotation of the word without suggesting why pique and nique are jammed together. Perhaps this is known only to the satirist who lampooned Pique-Nique and his crew during the War of the Fronde.

What became of Pique-Nique and les frères de Bacchique de Pique-Nique is a mystery. However, Pique-Nique remained sub rosa as a dining style for which chacun en paysant sa dépense or each participant pays a share. Fifty years later, the custom of cost-sharing at home was known as un repas à piquenique. It was officially included in Ménage’s standard French dictionary and defined as: PIQUENIQUE Nous disons faire un repas à piquenique pour dire faire un repas où chacun paye son écot ce que les Flamans disènt parte vital chacun fa part. Ce mot n eft pas ancien dans notre Langue & il eft inconnu dans la pluspart de nos Provinces.

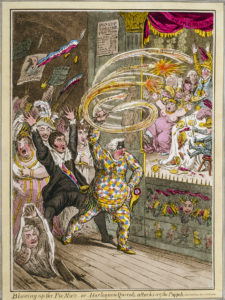

The English were hazy, or clueless, about piquenique until 1802 when Pic Nic surfaced as the name of a London club devoted to theatrical entertainment, eating, and gambling. Pic Nic members knew the Parisian custom, and the name was chosen because each member was required to pay a share of the costs and contribute a supply of wine and food. Like the French, all of Pic Nic’s dinners were indoors.

Unless knowledgeable of the French repas de pique-nique, the English were puzzled about its etymology, which was fuzzy even to club members. “Un de Derivatur Pic Nic?” a comic poem probably written by William Combe, added to the confusion:

James Gillray. Blowing up the Pic Nic’s (1802).

Philosophers in vain, their brains do twist,

To find the derivation of Pic Nic,

And most of them, I think, the truth have mist,

Because their brains were dull, or skulls were thick.

When the Pic Nics folded in 1803, their name widely circulated. They were made fools of. Nevertheless, their name and the notion of sharing attracted John Harris, a children’s book publisher, who named an outdoor wedding dinner a Pic Nic Dinner in The Courtship, Marriage, and Pic Nic Dinner of Cock Robin. To Which is Added, Alas! The Doleful Death of the Bridegroom. We’ll never know what he was thinking except that each guest brings a favorite food. Because animals don’t dine indoors, the dinner must occur outdoors.

Harris’s unintentional decision had far-reaching consequences. At a steady pace, picnic became the preferred word for an outdoor gathering, as it is today.

Featured Image: Édouard Manet. Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863)

1592: Thomas Nashe’s Strange News of the Intercepting Certain Letters introduces “potte-luck.”

1649: A musketeer named Pique-Nique was lampooned in Les Charmans effects des barricades, où l’amitié durable de la comapgnie de frères de Bacchique de Pique-Nique

1694: Giles Ménage defined piquenique, without attribution, as a meal at which guests share the cost in Dictionnaire Du Etymologique De La Langue Françoise. Pique-Nique, the musketeer, was forgotten, completely.

1745c: Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s The Confessions confides he dined tête à tête en piquenique” at home.

1755: Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language (1755) omits Picnic.

1772: Samuel Foote links nick-nack with Picnic in The Nabob.

1774: Lord Chesterfield first used the word in a letter to his son in 1748. The picnic was at an afternoon gambling salon in Hanover. In 1774, the word first appeared in print but went unnoticed.

1778c: J.J Rousseau dined en manière de pique-nique in a restaurant remembered in Reveries of a Solitary Walker.

1802: the London Pic Nic Society, a group devoted to gambling, theatrical performances, and gourmand dining.

1806: The Courtship, Marriage, and Pic Nic Dinner of Cock Robin. To Which is Added, Alas! The Doleful Death of the Bridegroom is the first outdoor dinner named a picnic in the modern sense.

1807: Washington Irving and James Kirk Paulding satirized women’s fashion using “picnic stockings.”

1818: Dorothy Wordsworth asked a friend. “By the bye, what is the origin of the word Picnic? Our Windermere gentlemen have a Picnic everyday.” The friends’ answer is unknown.

1825: Jean-Anselm Brillat-Savarin’s The Physiology of Taste, or Meditations on Transcendental Gastronomy, describes a halt on the hunt, Haltes de Chasse, but does not call it a pique-nique.

1828: Noah Webster’s American Dictionary of the English Language (1828) omits Picnic.

1862: Julien’s Les principales étymologies de la langue française is sure that piquenique is a corruption of the English pick an each.

1864: Edouard Manet’s Le déjeuner sur l’herbe conforms to French dentation that a picnic is an indoor gathering.

1867: “Excursion,” an essay in Harper’s Weekly, makes the case, “It is a cardinal belief with every man, woman, and child that a picnic includes pretty nearly the most perfect form of human enjoyment.

1897: E. Cobham Brewer’s The Dictionary Of Phrase And Fable writes that pic-nic derives from the Italian piccola nicchia (a small task), that is, each person being set a small task towards the general entertainment.

1897: Columbian Cyclopedia’s editors claim that the pique-nique is derived from English. picnic, and not vice versa.”

1911: The Encyclopedia Britannica tentatively suggests picnic may be a rhyming word or a small old French coin called a pique.

1913: Webster’s Revised and Unabridged Dictionary (1913) suggests an unsubstantiated link between “picnick” and “knickknack.”

1944: Osbert Sitwell condemns Picnic as an ugly word in “Picnics and Pavilions.”

1952 Fernand Léger’s series La Partie de Campagne conforms to French usage that a picnic is indoors.

1958: Eric Partridge’s Origins, A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English (1958) scants nique and repeats that pique is derived from the French word pique meaning to pick, to pierce, to pick up, to pluck, to gather, to choose.

1959 Jean Renoir’s Le déjeuner sur l’herbe includes two picnics.

2016: Goyard Bags advertisement explains that picnic is “a contraction of the expression “piquer (meaning to nibble) des nique (things of little value)” –was coined in the 13th century. During the Middle Ages, the Picnic is a frugal pursuit undertaken by French aristocracy while hunting or travelling.”