Rousseau was not thinking of a pique-nique when he wrote, “The turf will be our chairs and table, the banks of the stream our sideboard, and our dessert is hanging on the trees.” He knew that pique-nique was an indoor meal for which friends shared the cost. Sharing the bill at a tavern or restaurant was to dine en pique-nique; sharing a meal at home was un repas de pique-nique. For outdoor gatherings such as this one in Emile, Rousseau exaggerated and called it un festin, or a feast.

He continues, “The dishes will be served in any order, appetite needs no ceremony; each one of us, openly putting himself first, would gladly see everyone else do the same; from this warm-hearted and temperate familiarity there would arise, without coarseness, pretense, or constraint, a laughing conflict a hundredfold more delightful than politeness, and more likely to cement our friendship.”

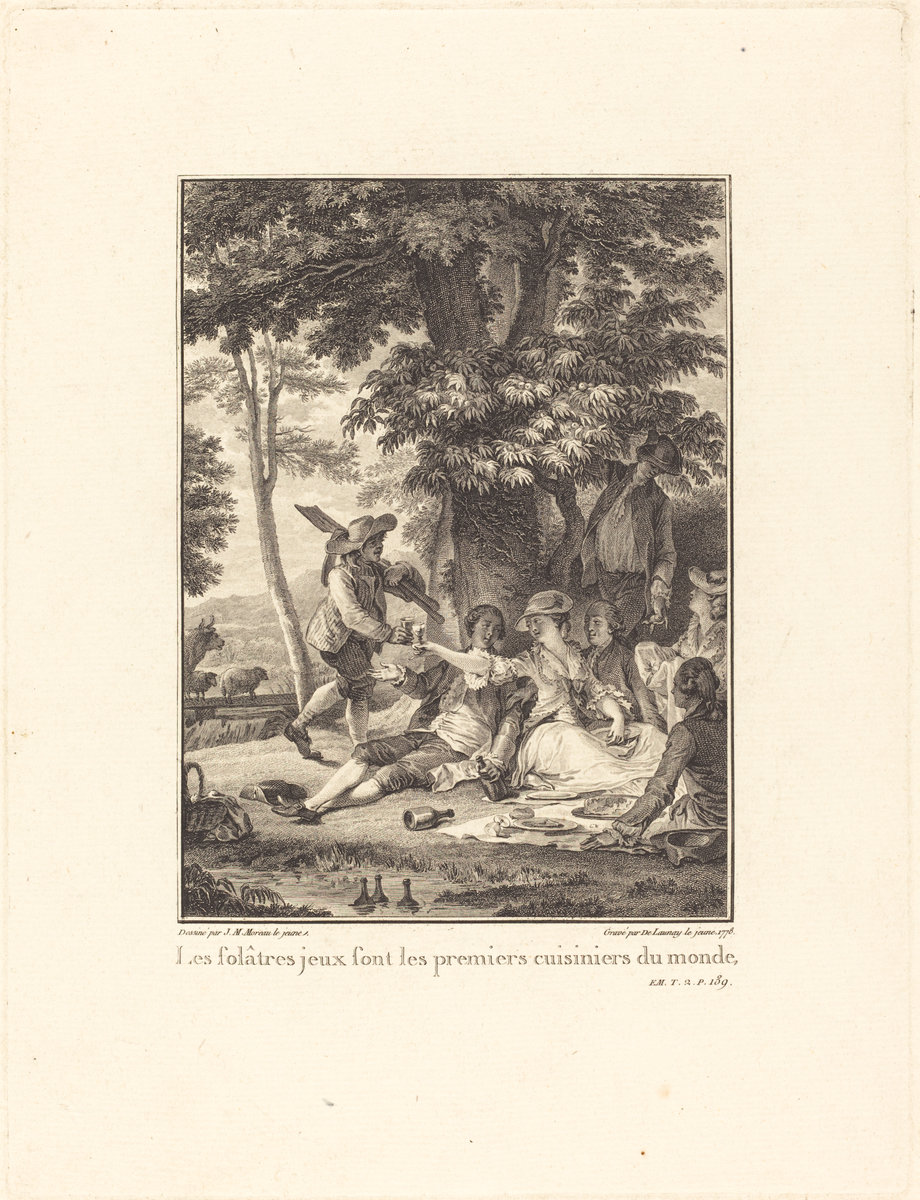

An illustration for Emile, titled “Les folâtres jeux sont les premiers cuisiners du monde,” or “Playful games, sportive games, frisky games are the best chefs in the world,” captures the picnicky qualities of alfresco dining. Couples are sitting on the grass in the shade of a great oak. They have been eating and drinking, and now seem boozy and vaguely amorous. Rousseau suggested “a glass or two of good wine,” but Moreau ups the ante, and in addition to the empty bottle on the cloth, three more bottles are cooling in the stream. Moreau also scants Rousseau’s advice and goes (very) heavy on the wine.

Because Rousseau was a vegetarian (and was particularly fond of white foods!), the menu might have been milk, cheese, vegetables, fruits, bread, milk, sweet cream, and pastries.

Featured Image: Robert Delaunay. After Jean-Michel Moreau, the Younger. Playful games are the best chefs in the world [Les folâtres jeux sont les premiers cuisiners du monde] (1778), etching and engraving.

See J.J. Emile, or On Education (1762), translated by Barbara Foxley. New York: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1911; http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/5427/pg5427.html