Zola’s pique-nique at the Moulin-d’argent [Silver Windmill] is not a picnic in our contemporary sense. According to French usage, it was a style of dining indoors. When Gervaise Macquart and Coupeau host their wedding party, each guest is expected to pay a share of the cost of food and wine.

For newlyweds, Gervais and Coupeau, sharing is the most practical way for dinner. Zola explains that “Gervaise did not want to have a wedding party! What was the use of spending money? Besides, she still felt somewhat ashamed; it seemed unnecessary to parade the marriage before the whole neighborhood. But Coupeau cried out at that. One could not be married without having a feed. He did not care a button for the people of the neighborhood! Nothing elaborate, just a short walk and a rabbit ragout in the first eating house they fancied. No music with dessert. Just a glass or two and then back home.” The dinner is a success. They all get drunk and laugh that the ragout “mews,” a not-so-sly suggestion that it’s made with cat meat. But when they must ante up, the guests do not contribute enough to cover costs.

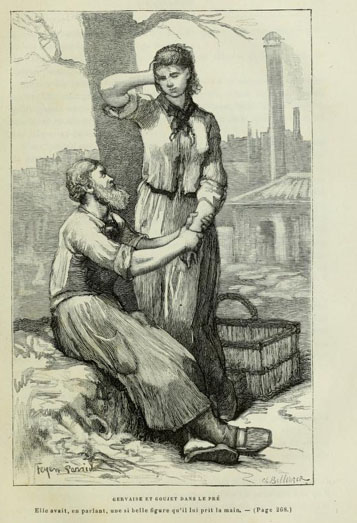

As foreshadowed by the end of the wedding party, the marriage is a failure. Coupeau is a beast; Gervaise declines. On the verge of economic, personal, and marital despair, Gervaiseand Goujet, her old admirer, meet in a meadow of Montmartre, then only a Paris suburb. Again, Zola refrains from naming the meeting a picnic, or for that matter, anything but a meeting of two old friends outdoors.

Gervaise meets Goujet as he leaves work. They fall into conversation and walk past the factories until they enter a small meadow where they sit on a dead tree on bare ground splotched with tufts of grass. Gervaise says it’s like being in the country, but she knows better. “They turned into a vacant lot between a sawmill and a button factory. It was like a small green meadow. There was even a goat tied to a stake. “It’s strange,” remarked Gervaise. “You’d think you were in the country.” They went to sit under a dead tree. Gervaise placed the laundry basket by her feet.

Goujet asks Gervaise to run off. Gervaise is confused, “What do you mean?” “We’ll get away from here,” he said, looking down at the ground. “We’ll go live somewhere else, in Belgium, if you wish. With both of us working, we would soon be very comfortable.”

Gervaise flushed. She thought she would have felt less shame if he had taken her in his arms and kissed her. Goujet was an odd fellow, proposing to elope, just the way it happens in novels. Well, she had seen plenty of workingmen making up to married women, but they never took them even as far as Saint-Denis.

“Ah, Monsieur Goujet,” she murmured, not knowing what else to say. “Don’t you see?” he said. “There would only be the two of us. It annoys me having others around.”

Gervaise is confused by the suddenness of this proposal; she refuses Goujet because she is a married woman. He nods but then suddenly kisses her, crushing her in his arms. At a loss, he begins plucking tufts of grass and daisies and throwing them into her empty laundry basket. By the time they regain their composure, her basket is full of flowers.

Gervaise and Goujet’s interlude in Montmartre is neither idyllic nor picnicky.

Featured Image: August Bellenger. “Gervaise and Goujet in the Meadow.”

See Emile Zola. L’Assommoir [The Dram-Shop]. 1870. Edited by Translated by Edward Vizetelly. London: Chatto & Windus, 1897. Also illustrations of Zola novel at https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b22001295