Elliott’s moral tale The Mice and Their Pic Nic failed to persuade readers that a “pic nic dinner,” especially in London, is sinful. Elliott’s readers were expected to recognize her mouse story as an adaptation of Aesop’s fable “City Mouse and the Country Mouse.” The link to Horace’s satire “Mus Urbanus et Mus Rusticus” is important because Elliott suggests a comparison of contemporary London to the decadence of Rome.

Long forgotten, Elliott’s The Mice and Their Pic Nic is now remembered as the second published reference to a picnic in English. It appeared in 1806, three years after The Happy Courtship, Marriage, and Pic Nic Dinner of Cock Robin, but unlike the earlier children’s book, Elliott’s “pic nic” follows the French custom of dining indoors.

Because the story is a puritanical warning against sinful behavior, Elliott was probably advised by her experienced publisher, William Darton, to use a “pic nic” as a metaphor for showing how gluttony will have grievous consequences. Darton’s model was the London Pic Nic Society, a scandalous gossip item during 1802/3. [See discussions of the Pic Nic Society, The Happy Courtship, and James Gillray posted elsewhere on PicnicWit.com]

Presuming that most of her readers, children, and adults, would be unfamiliar with a “pic nic” dinner, Elliott covers this gap with a definition:

What was meant by a Pic Nic, they could but wonder

Yet ventur’d no question for fear of a blunder

When they did understand, how they open’d their eyes.

For the guests to bring food was indeed a surprise,

“Well, surely,” thought some, oar [our] old country ways

Are more gen’rous by far, for with us the host pays

While here, those invited, subscribe to the treat,

And visit their neighbour to eat their own meat!

Curiously, Elliott does not follow her definition. The Country Mice arrive empty-handed, expecting to be hosted by the London Mice, who have promised an epicurean Christmas dinner. Used to corn kernels, the Country Mice are feted with cold soups, sweetmeats, fricassee chicken, cold bacon, pickles, whipped cream, plumb-cake, cheesecake, custards, and Cheshire cheese. There is some resistance to the new foods, but when they join in the feast, they seal their fate. For though you might enjoy such a meal, Elliott means it to be gluttonous and so sinful that it must end badly—and abruptly:

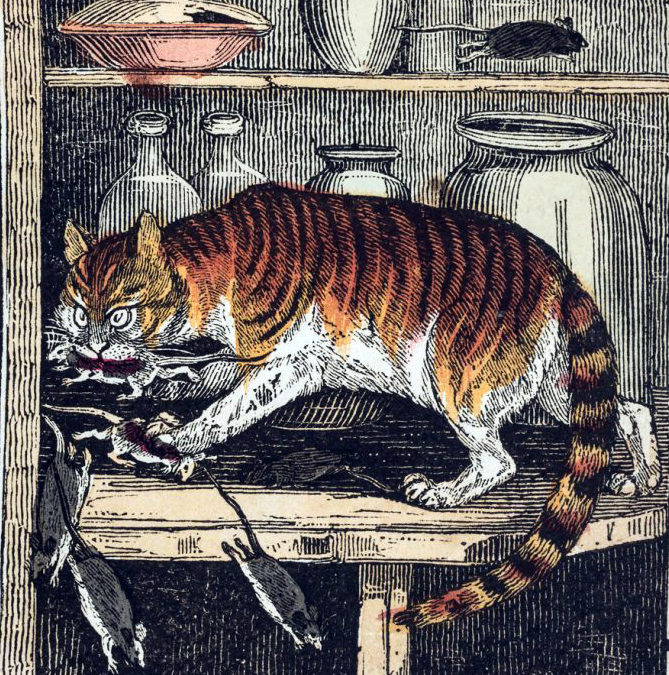

When sudden the cupboard door wide open flew,

And in rush’d a fierce looking, large tabby cat,

Who advance’d, with huge strides . . .

In the chaos, all that is heard are the shrieks, and groans, and crunching of bones.

Cook kills a mouse. The illustrator for the 1813 edition is unknown.

Featured Image: Tabby’s “pic nic dinner.” (1813 edition)

The few Country Mice that manage to return (all of them scared) are admonished for being seduced by the promise of luxury at a “pic nic” dinner in a London townhouse. OldWheatears (the elder Country Mouse) delivers a stern sermon to the wanderers:

I’m assured as for man, so for mice, there’s a station.

That seldom is changed but for mortification.

And if we but look round the world, we shall see,

No species, from evils entirely free,

For happiness not to the rich is confin’d,

But chiefly depends on the worth of the mind.”

The impact of Elliott’s moral tale failed. Readers were not persuaded that a “pic nic dinner” was a grievous sin any more than the readers of Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre were convinced that naughty girls would go to hell.

*At the start, twenty mice depart from their Devonshire barn for London. Ten arrive safely in London, but only four manage to return.

See Mary Belson Elliott. The Mice and Their Pic Nic. A Good Moral Tale, &C. By a Looking-Glass Maker. London: W. and T. Darton, 1809. Unacknowledged in the first edition, Elliott went on to a successful career using Elliott, her married name Elliott. The illustrator for the 1813 edition is unknown.